One Hundred Years Ago this Spring: Lighthouse Stars, Island Universes, and the Great Debate of 1920

- Douglas MacDougal

- Apr 1, 2020

- 4 min read

Updated: May 27, 2020

A century ago in Washington DC, at a National Academy of Sciences’ symposium put together by George Ellery Hale, Heber Curtis and Harlow Shapley debated the size and nature of the universe.

It seems odd that there should be a debate about such fundamental matters now. It reminds us of the 19th century Huxley-Wilberforce debates on Darwin’s evolution by natural selection and the descent of man from apes. Nowadays we are used to less flashy swordplay in the staid halls of science. The work of science typically proceeds from observation, the collection of data, mathematical modeling and analysis, and the quiet publication of papers. There are private and published discussions of techniques, possibilities of error, questions about assumptions, and occasional presentations at conferrences, usually upon narrow fields of expertise. All very businesslike and measured. But here in 1920, the debate was about the nature of the whole universe.

Curtis and Shapley were interesting fellows; people you’d like to get to know. Each Had respectively studied things old and small. Curtis, an astronomer from Lick Observatory, was a good debater, confident, well spoken, with a strong voice. He had studied Greek, Latin, Assyrian, Hebrew, and Sanskrit at the University of Michigan. He got his doctorate at the University of Virginia in 1902. Shapley, from Mount Wilson, was a passionate amateur myrmecologist, employing his daylight hours to collect ants around the grounds of the observatory and elsewhere in the world. He excelled in math and physics at the University of Missouri and completed his in astronomy doctorate at Princeton under Henry Norris Russell, in 1913. He agreed to debate the scholarly Curtis at Hale’s urging, but public speaking was not his strength. Yet making a make a good mark at the speech might help land him a hinted-at offer as the new director of Harvard College Observatory.

In the spring of 1920 two main issues swirled in the air. The first was whether our Milky Way galaxy was all there was, i.e., the entire universe. The myriad little spiral smudges that appeared on photographic plates were, in Shapley’s view, parts of our own galaxy, within it. They were not resolvable into stars, and Adriaan Van Maanen and had published evidence that these spirals must be close to us. He could measure rotation rates in some of the larger galaxies, like M33. This would be implausible if they were remote. Shapley relied on Van Maanen’s measurements to demonstrate his point and prove Curtis wrong. Curtis, to the contrary, didn’t trust Van Maanen’s data. He firmly believed these spirals were ‘island universes’ – each its own remote galaxy swarming with stars of their own. But the evidence for that view, admittedly, was scarce.

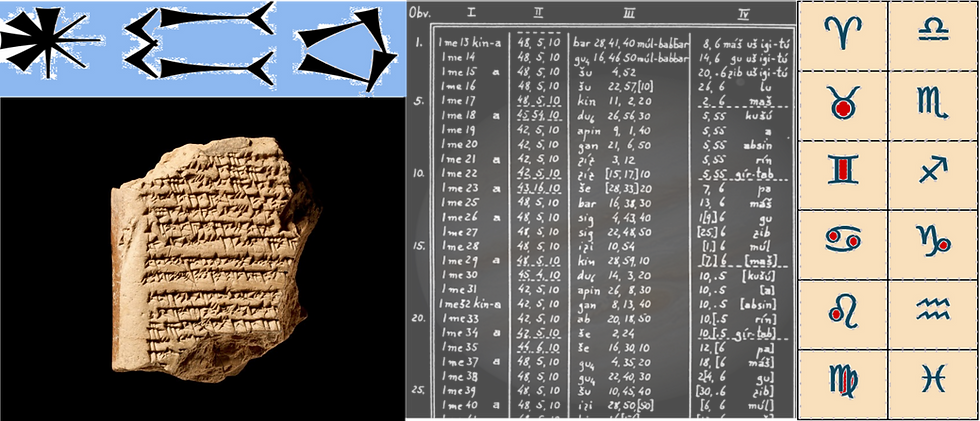

The second great issue was the size and arrangement of our own galaxy. Shapley had been using the ‘lighthouse stars’ (as James Jeans had called them) – Cepheid variables – to measure the distances to the ghostlike, beautiful globular clusters which populate the sky more or less near the plane of the Milky Way. When Shapley plotted their distances with their directions, they appeared to cluster around the region of the densest Milky Way star clouds of Sagittarius, which he concluded must be our galaxy’s center. If he was right, the news would be sensational (in Hale’s words). It would show, once again, that we in our solar neighborhood were not at center of the universe, a still-cherished view held over from the days of Aristotle. Mankind had just barely (within the last 300 years) come to terms with the Copernican fact that the earth is not the center of the solar system; now to find that the solar system is not the center of the galaxy would be yet again disconcerting. Shapley’s data also suggested that the Milky Way was far larger than anyone had anticipated.

And so they debated, in an audience loaded with luminaries including Albert Einstein. For his part, Shapley didn’t regard it a true ‘debate’ because they were arguing two different positions at cross purposes. Curtis came to talk about island universes; Shapley to present his views about the center of the Milky Way Milky Way and its size. In retrospect the debate was a turning point in the modern history of astronomy. Science was on the threshold of learning some dramatically new things: the debate set the table for the educated public on two seminal issues in astronomy, and prepared it for what was to come.

It turned out that Von Maanen’s measurements were wrong, and Shapley was wrong to rely on them. While they were talking in Washington, Hubble was guiding long, deep exposures with the 60 and 100 inch Mount Wilson telescopes. He was only a year into his seven year project of photographing the outer arms of the Andromeda galaxy and M33, with. His plates resolved those galaxies into stars, revealed novae, and showed about forty Cepheid variables in both. These lighthouse stars settled the case that those galaxies were indeed far-distant island universes. Shapley later said in his reminiscence, Through Rugged Ways to the Stars, p.80 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1969), “I stood by Van Maanen. I was wrong, not so much in any statement that I made, but in the inference that the spirals must be inside and not outside our system.” He added: “They wonder why Shapley made this blunder. The reason he made it was that Van Maanen was his friend and he believed in his friends!” It is these subjective factors that often shape the direction of science, and make investigating the process of science so interesting! Curtis was right about island universes, but Shapley was right about putting the galaxy’s middle far from us in the constellation of Sagittarius (and he did get the job at Harvard College Observatory).

Edwin Hubble’s revolutionary work would show within a decade of the debate that not only were there other island universes but that they were receding at rates proportional to their distances, opening a whole new vision for man to comprehend, that of an expanding universe..

Comments